FREETEKNO & CZECHTEK 2005

Lukas Wimmer, English translation by Jana Duckwall

Lukas Wimmer is a long-standing member of the Czech Republic’s Free Tekno scene. He recently acquired his M.A. in Public and Social Policy from the Charles University in Prague. The following article is an excerpt from his thesis. He attended CzechTek 2005 and was witness to its conflicts.

From: JanaDuckwall@-----

Subject: Czech/English Translation Needed

Date: June 26, 2007 3:34:49 PM EDT

To: translate@veneermagazine.com

Hi,

I can help you with the czech translation. My name is Jana and my cell is -----

Have a good day

How did you find out about the article anyway? Do you speak czech at all? Just curious…

Jana

-----

At the end of the ’90s, the Czech media exploded with news of an annual invasion of bizarre individuals. They showed up every July or August and occupied private properties for several days in a row with illegal techno parties (raves). These individuals stood out for their unusual appearances and taste in music, and rumors spread that their raves were filthy and ridden with drugs. For the ravers, it was the cultural and social event of the year. But for locals and the police, it was like a nightmare that happened year after year.

In 2005 the Czech police decided to put a stop to the raves. However, they ended up using more force than they needed to. People all over the world started talking about Freetekno, the controversial new social phenomenon.

This article explains what Freetekno is in its essential form and aims to shed some light on the values it represents, its ideologies, behaviors and motivation.

Rave And Freetekno

“A rave is a phenomenon that does not exist within the rules of society, it is the creation of a separate space.”[1]

“Rave” means dance party, or the type of music played at a dance party. The actual concept of the rave is not new. Dance is a ritual, a traditional and celebratory form of worship to bring about relaxation and psychological healing. “At the base level, rave is very comparable to American Indian ceremonies…where music is the key toward putting one self into a unique emotional and psychological state.”[2] In the context of the modern dance scene, “rave” refers specifically to an illegal party. Following the segregation of the commercialized club scene, a fundamental segment of rave culture demanded free access to parties, adopting the label “Freetekno.” Freetekno is an offshoot of the dance scene, linking electronic dance music with traveling, spirituality, do it yourself (DIY) principles and drug culture into a larger, more global meaning.

The Free Teknival

Teknival (tek-ni-val) noun—1. An artistic and musical festival that usually takes place in the European countryside. 2. A celebration of a musical sub-genre called Techno, including what was left after the crash of the British acid house scene.

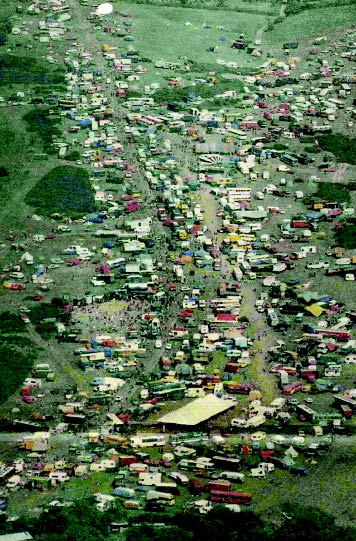

The Teknival in the Czech Republic is represented by an organization called CzechTek, which is closely tracked by the media. Sound systems are set up in a secret place that for a few days turns into a “festival town,” with its own social conventions based on principles of the free party. A sound system is not just a set of speakers—it’s a group of people creating a scene by playing and performing. Sound systems originated in Jamaica, at the beginning of the Dub scene. They’re the nucleus of the Freetekno community, just as families are in traditional society.

Teknivals such as CzechTek are known for their relaxed atmosphere, in which everyone respects the basic principles of DIY culture, not only in regard to the sound systems, but also to the entire model of music production. Techno is not the only type of music at CzechTek; starting in 2003, more diverse groups of people began to attend and new genres of music (hip hop, punk, hardcore and ska) were represented.

Unlike the commercial club scene, Freetekno doesn’t hinge on the names and prestige of individual DJs. At a club, a well-known DJ comes to perform, while Freetekno allows a group of people (or sound system) to organize the party. Sound systems are often referred to as tribes (as with one of the most famous British sound systems, Spiral Tribe). This makes sense, because like a tribe, a sound system is a community, with a social structure that depends on a feeling of connection, common identity and communication.

The rave scene—and, later, Freetekno—was in its pure form always an underground movement. Its ambition was to exist outside mainstream society. From the beginning, it was all about escapism.

… The elements are all connected, most having in common longing for escape out of unpleasant reality. This phenomenon points toward a forgotten relationship between strict social organization (one based on strict Christian roots) and the secular wish for escape (even for a while) into the world of instinct and basic elements, interfering with magic and rituals… Dance was always its original substance.

In its beginning the dance scene became a refuge for different social groups, especially people with different sexual orientation. Tolerance is the base for success of a party, the clue for interpersonal relations, and the bridge over taboos and ideological stereotypes. What are the principals, values, goals and needs that define the Freetekno sphere within a social space? It is an emphasis on autonomy, disentangled from the gear ravers need to make their sound systems mobile and to occupy free suburban spaces—everyone who can respect others is welcome.

“Don’t hate the media, become the media.”

Jello Biafra, the Dead Kennedys

The DIY scene was born when people started to realize that the only way to make something happen was to do it oneself, whether they were protesting against highway construction or campaigning for the equal rights of minorities. Sound systems, then, offered a form of self-realization in all aspects of human creativity, while the “rave” was an opportunity to show it to others. Friends either pooled money for music equipment, projectors and stroboscopes, or built them themselves. Those unable to do so painted canvases for use as backdrops, or built tents for people to escape the rain.

Garbage and mess left behind after Freetekno events are one of the main arguments the public uses against organizing such parties. While Freetekno calls for a maximum level of personal freedom and respect for others and offers a wide space for individual behavior, it also shirks responsibility for individual disorder. Unfortunately, even if the Freetekno scene declares responsibility for after-party cleanup, it rarely happens.

The Political Ideologies of Freetekno

“The idea that [rave] culture has no politics because it has no manifesto or slogans, it isn’t saying something or actively opposing the social order, misunderstands its nature. The very lack of dogma is a comment on the contemporary society itself…its definition is subject to individual interpretation: it could be about the simple bliss of dancing, it could be about environmental awareness, it could be about race and religions and class conflict…it could be about reasserting lost notions of community—all stories that say something about life in nineties.” [Collin 5-6 in Steins, E].

From its spontaneous beginnings, Freetekno was not about politics. But now different views abound within the Freetekno community. Some see Freetekno as a fight against an unfair system, while others just anticipate a weekend party. People often call ravers anarchists, but that position is short-sighted. However, it is important to note ravers’ roots. The first Czech sound system came out of a squat called “Ladronka,” which supported anarchist newsletters and actions. Meanwhile, the British sound system Exodus (established in June 1992) met in an abandoned farmhouse, where they took in the homeless and farmed their own produce.

Whether or not ravers are anarchists, Freektekno is about living autonomously. A related concept is TAZ, or Temporary Autonomous Zones; street parties, squats and rave parties are just a few examples of this kind of space. The term TAZ has become famous through the work of Hakim Bey, who proposes the anarcho-political tactic of creating a temporary space that avoids formal structural control. Bey uses different historical and philosophical examples, leading to the conclusion that the best way to introduce a non-hierarchical system of social interactions is by strongly emphasizing the present. In simple terms, TAZ are an occupation (intrusion) of space to create entertainment—illegally and with friends. A typical example is the early ’90s rave party, lasting usually just for a few hours, with massive sound systems and ravers filling abandoned warehouses. No permission was necessary, no taxes were paid—you only had to let your friends know when and where to show up.

The Rising and Splitting of the Dance Scene

The British sound system Spiral Tribe was partially responsible for the massive ideological spread of Freetekno at the beginning of 1990s, largely due to their lyrics: free party, free people and free future.

After the implementation of the Criminal Justice Act (CJA) in Britain in 1994, sound system culture spread to other Europeans countries, while it Britain it went underground. Some sound systems moved back into the clubs, becoming mainstream; in time, the label “raver” was changed to “clubber.”

Czech Republic

The year 1994 was important for the Czech techno scene: The events of that year’s Love Parade and May Day events in Germany, as well as the Czech Republic’s own free parties, had a huge influence on the country’s commercial club scene.

The country’s first sound systems appeared at approximately the same time, since Spiral Tribe and Mutoid Waste Company were escaping from Britain after panic caused by the CJA. The members of Spiral Tribe commented on the situation, saying, “the result [of the CJA] is an exodus to the promised land, Europe and beyond, as England tightens the screws, enforces its consumer monoculture of civil obedience and staticism, the energy of the scene flows out like tendrils of techno energy and here we are, it’s the late twentieth century and Spiral Tribe and the Multoids are in a scorching field way out in the Czech Republic, in Eastern Europe.”

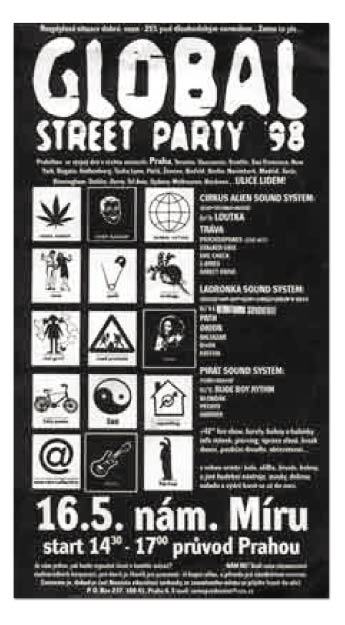

This traveling community found its first listeners among punks and squatters, particularly in “Ladronka,” the famous Prague squat. From that point, the Czech scene was shaped by a few active sound systems; for example, pioneers Direct Drive and Technical Support. Another important system was Mayapur from Dobris, who participated in the first big technivals. The most significant sound system was, in the beginning, Cirkus Alien, based in Ladronka; it was the only one in the Czech Republic that also claimed political interests. Most of the parties of this era took place at Ladronka and a nearby abandoned estate, Cibulka. Eventually, parties moved to dance clubs and abandoned army land outside Prague.

The traditional Czech celebration of spring, the “Burning of Witches,” became a phenomenon of the Freetekno scene, and a synonym for the first open air parties of the year. In 1998 the Czech Republic was introduced to more music from mobile sound systems, as Prague hosted the Global Street Party. It took place in 36 other spots around the globe and was politically charged against global capitalism and its consequences. Just a few months later came another similar event, Prague’s Local Street Party.

By the late 1990s, parties were becoming more and more popular, and by the time of CzechTek ’99, there were about 30 sound systems at the Teknival; although mostly from abroad, about 10 of the sound systems were Czech. Three years later, the number of Czech sound systems had climbed to 50, and the number of parties was rapidly growing. By the year 2005, several parties took place simultaneously almost every summer weekend.

Specifics of Czech Freetekno

Some special conditions distinguish the genesis of the Czech Freetekno scene from its Western counterparts. First, the Czech scene is unique, as a result of the relative absence of migratory sound systems; the Czech Republic is a small country, and traveling within it does not make much sense. Rather, sound system members are recruited from the working class; they’re mostly people who consider music a hobby rather than a source of income. Cirkus Alien is one exception; the group traveled to France, Italy and Spain in the late ’90s.

The Czech Freetekno community was a haven for young members of the middle class, who participated in the parties for fun (with no political motives). Only a small percentage of the Freetekno scene claim to adhere to ultra-left wing politics, something that is visible by their presence at anti-globalization events and in their support of the left-wing press.

Another idiosyncratic characteristic of the Czech scene that cannot be overlooked is the Czech tradition of drinking alcohol. Almost every free party provides a great deal of it; the proportion of alcohol to other, more illegal drugs (if they are even present) is radically disproportionate to the West. The Czech Freetekno scene is an isolated, non-traveling culture, and generally much more conservative toward drug use.

CzechTek

The Freetekno festival CzechTek was the yearly focal point for everyone within the free party community. People viewed it as more than just a party—it was a platform to share information. It was a place to meet people from abroad and get inspired by their ideas. On the other hand, as the popularity of the event increased, the party site’s surrounding community came under pressure. Admittedly, most of these Teknivals were organized without proper permission from local landowners. The CzechTek solution was risky: Organizers waited until the last moment to announce the event to officials, making it impossible for local authorities and inhabitants to pressure landowners or ban the festival.

Fortunately, the first three festivals (starting in the summer of ’94) took place without any problems and went almost unnoticed by authorities, with only a few encounters from neighbors. In the next two years, however, the media started to cover the event and began to spin the dance party, and all parties like it, as dangerous drug meccas.

Partially due to the media, the police kept a close watch on the festivals in years to come (1999 to 2004), although no incidents were reported. The 2003 CzechTek took place in an empty field near the small village of Ledkov and accommodated nearly thirty thousand people. It lasted for 10 days, even after officials tried to shut it down due to noise violations.

The 2004 CzechTek took place in Tachovsko. The people who lived nearby began to protest almost immediately, and the whole situation was documented on Czech television. Eventually, the festival was shut down by police (due to a dodgy rental agreement). But people were already taking off by then, so there were only a few conflicts. Ironically, one participant who was taken into custody was organizing an after-party cleanup.

CzechTek 2005

“The truth is on our side, naturally.”

-Czech police spokesman, regarding CzechTek ’05

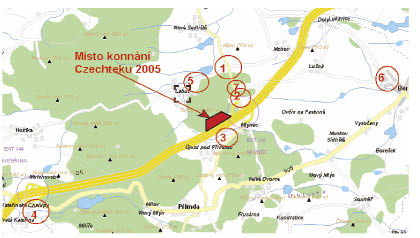

The 12th annual CzechTek music festival was planned to take place in July and August in Mlejnec in the Tachovsko district. The public was curious about the event, given the previous year’s heavy media coverage and police intervention. Everyone seemed to have strong opinions about the police action in 2004: Some condemned the violence, while others supported it.

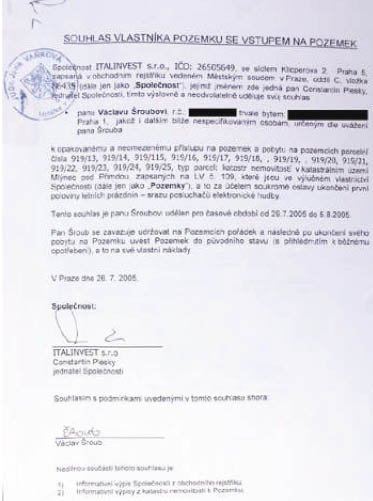

Police prepared for CzechTek 2005 by printing pamphlets in several languages warning participants about the risks of unlawful behavior. The public accepted the precautions, which were standard for big events like this. Legal authorities assumed this Teknival would be illegal and would lack any kind of formal agreement with the landowner.

Friday 7-29-05

Around 2pm on Friday, July 29, 2005, the police discovered the exact location of the party during a routine traffic inspection. An operating headquarters was immediately established within the division of Tachovsko. Later that day a truck carrying a large amount of music installation and gear got stuck on a local highway. It was rented by one of CzechTek’s organizers for a “formal private party,” as it was described to officers at the local police station. The organizer also mentioned that, according to criminal law, a meeting had been held in Prague and an agreement had already been made about the use of this private lot for a private summer party and meeting of electronic music fans called CzechTek.

Nevertheless, the police restricted entry to the party, causing a 10-kilometer traffic jam. To justify the blockade, they claimed to doubt the proper use of the entry road and alleged unclear relations with the owners of nearby fields.

Meanwhile, the person who was renting out the land in question visited the police station in Prague to confirm that a private party for “the celebration of the end of the first half of the summer holiday” could indeed be held on his land. Still, even after the police obtained the owner’s verification, the blockade of the site continued. The land surveyor coming to delineate the borders was not allowed in, and even necessities such as a water truck and mobile toilet stayed out. At the same time, owners of surrounding lots asked for police protection of their properties.

The Czech police press spokesman said, “It is not important now if we have the agreement of verification from the owner. What’s important is that we do not have a permit from the owners of surrounding land, because there is no public entry road to the concerned land.” The police also urged incomers to stop using the freeway ramp leading to the contested road. When people didn’t comply, they closed the road completely.

Later in the afternoon, a water cannon was brought to the site. Some cars were already leaving, but new people continued to arrive by car or train. Many of the newcomers found it impossible to even get close to the site because of the blockade. People left their cars in surrounding fields or roads and tried to walk to the site.

7-30-05

According to the police report, 3,000 to 5,000 people and over 500 vehicles were on the site, many over the boundaries of the rented land, and more were pouring in. Throughout the morning, more complaints from locals were filed, and several authorities visited the site.

A few minutes before 4pm, the police issued a press release about their anticipated action. Shortly afterward police cars entered the festival area, and officials asked people to leave (in several languages). Most people didn’t even react; it was difficult to hear the police over the loud sound systems. At about 4:30pm police started to clean the area. The media (Czech TV Nova) were not allowed to enter for “safety” reasons. The first police intervention ended at about 8pm. By that time, most of the participants were gathered at the rented land.

Sound systems encouraged people to create a peaceful resistance by remaining on the site and passively showing that they don’t agree with the police action. This didn’t last long, though. The entire area turned into a smoke-filled battlefield; the police also used the water cannon. These were the violent means they used to get the situation “under control.” Those who were not brutalized were forced to leave. By 11pm, the police had seized 8 pieces of music equipment for the criminal record.

The intervention at CzechTek 2005 sparked quite a reaction. The very same day it happened, people were already gathering in front of the Czech Ministry of Interior Affairs to protest. Several thousand people threw eggs and paint at the building. Small protests were held, too, at the Czech Embassies in Helsinki, Dublin, Paris and Berlin. In the Czech Republic proper, the demonstrations took place mostly in Prague. The last big protest was called “The Street Rave Parade” and happened in the end of September 2005. Considering the scale of the event—about 3,000 people and a slew of decorated cars—the media did not pay very much (if any) attention.

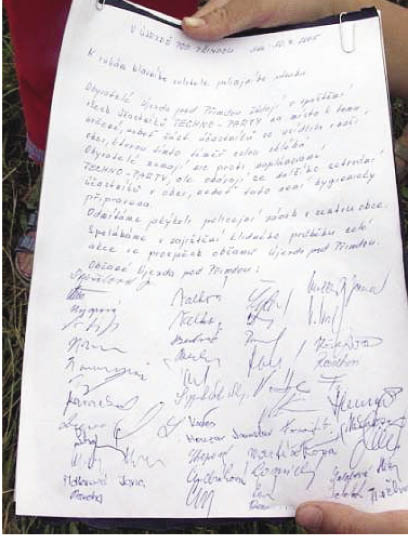

Protesters demanded an explanation of the police action, mainly why the person renting the field and his guests were not able to access their own site, even after proving it was rented legitimately. They also wanted to know which article of law justified the police’s decision to brutally expel people from a place at which they were staying legally.

Protesters also requested the formation of an independent commission to evaluate the police action. Further, an appeal was made to the Czech government to make a formal statement regarding the authorization and legitimacy of such an act.

The demonstrators were supported by a few right wing parties, and, later by extreme left wing and anarchist groups. Supporters also emerged from the Czech cultural scene.

[1] STEINS, E. Peace, Love, Dancing and Drugs: An In-Depth Sociological Analysis of

Rave Culture in America.

[2] STEINS, E. Peace, Love, Dancing and Drugs: An In-Depth Sociological Analysis of

Rave Culture in America.